The Economist

In the 1960s, performance artists made Seoul a surprising hotbed of the avant-garde

AS A young artist starting out in what is now North Korea, Seung-Taek Lee recalls being asked by a party official if he could make a statue of Kim Il-Sung, the new country's founding dictator. It was a painful business, and his first few efforts collapsed. But the figure he eventually produced so impressed the comrades that he was exempted from military service. A statue of Stalin followed. Then in 1950 he fled to the south.

A pioneering conceptual artist, Mr Lee, now 85, is one of the stars of a show at London’s Korean Cultural Centre (KCC), highlighting the birth of avant-garde performance art in South Korea in the late 1960s. His delicate white “Paper Tree” catches the light from the window, while a series of colour prints captures the spectacle of his often wind- or water-based performances and land art.

By 1967, South Korea had barely recovered from the war that laid waste to the peninsula in the previous decade. Ruled by Park Chung-Hee, who seized power in a coup, it was desperately poor, with GDP per head below $200 (equivalent to about $1,500 today). Hardly ideal conditions, one might think, for avant-garde art. Yet suddenly groups of young artists began staging “happenings” to John Cage’s music. In what seems a riposte to Yves Klein, who used naked women to make his paintings, women were taking the lead, relishing their nudity as an assertion of female power.

Intriguingly, it was the presence of the American army that let these radical artistic ideas spread. With New York the capital of cutting-edge art, South Korean artists could get black market copies of magazines such as Art in America, if not hot off the press, then shortly afterwards. They formed groups to discuss and unpick the ideas. These also flowed in through Japan, the colonial power in Korea from 1910 to 1945, and for decades a gateway for Western culture to reach Korea.

The Dada-inspired “Happening with Vinyl Umbrella and Candles” (1967), which alludes to the bombing of Hiroshima, and the following year’s “Transparent Balloons and Nude Happening” by Kang-Ja Jung, in which the artist sat topless, while the audience attached balloons to her, then popped them, are seminal works from the era. Ku-Lim Kim staged “Sex on the Piano”, in which a copulating couple created a sound work when their feet accidentally touched the keyboard. The mocking, voyeuristic tabloid press couldn’t get enough of it. “No kidding!” ran a piece in the English-language Korean Times, “It takes balloons, a semi-nude woman’s body, loud beats and psychedelic lights to make some graduates of art schools claim they have produced a work of art.”

Before the mood darkened considerably in the 1970s, the authorities seem to have viewed it all as youthful mischief, to Ms Jung’s intense irritation. Of “Murder at the Han-Riverside”, a performance involving earth, water, and angry slogans, she says “The message was: ‘Bury the older generation.’ We were serious about ‘murdering’ the cultural leaders.”

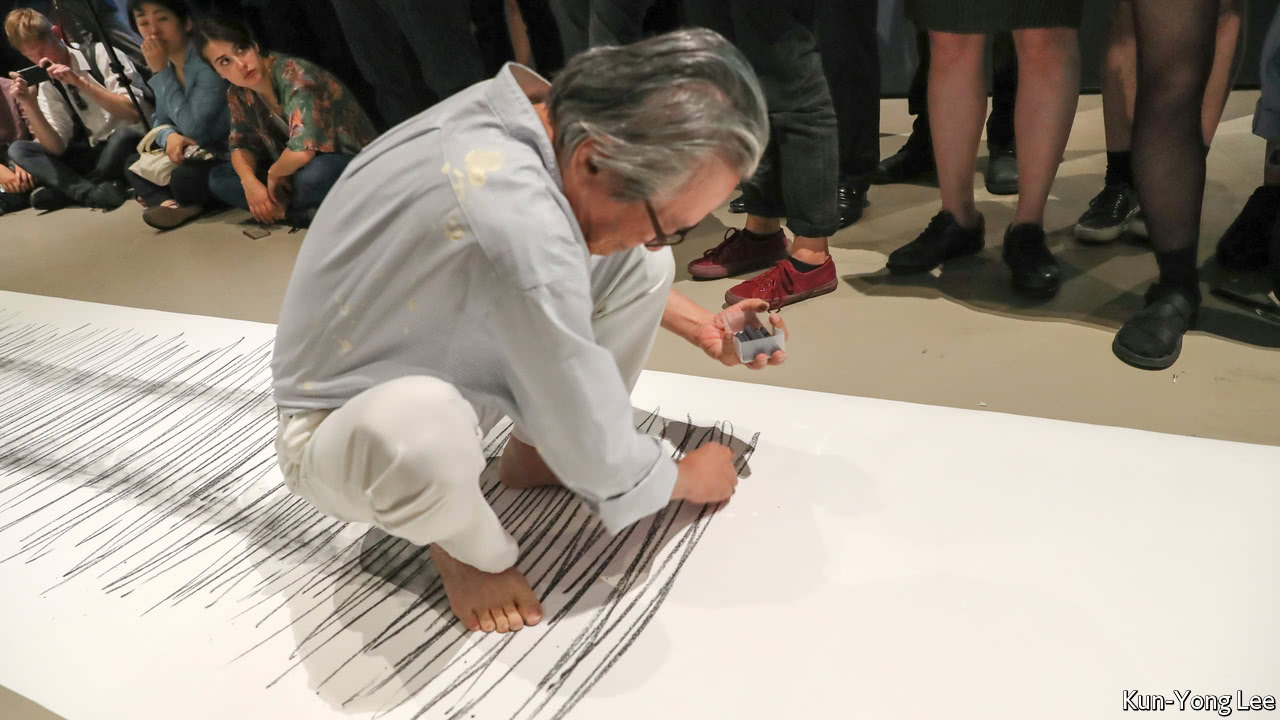

At the London show, past and present were united on the opening night in the presence of Kun-Yong Lee, now an honorary professor at Kunsan National University. The room fell silent as this second Mr Lee stepped up to a blank black canvas and put on a shower cap. Then, with his back to the canvas and brush in hand, he began to paint “blind”— over his shoulder and to either side of his body: a new instalment in a series begun in 1976 was taking shape before the audience’s eyes.

It is thanks largely to the efforts of Mi-Kyung Kim, an art historian who died last year, and the newly established Asia Culture Center in Gwangju that the stories of these pioneering artists are now being told. “There are so many gaps in what we know,” says Je-Yun Moon, a curator at the KCC. “I found that performance artists in Korea today don’t know about the 1960s people, and that became a motivation for the show.”

The exhibition includes younger artists, the best known of them being Lee Bul, whose intense “Abortion” video arguably pursues the “discussion” about women’s control of their bodies that Ms Jung began with her Balloons piece. But, really, the show belongs to the older artists.

An hour after his stint at the black canvas, Kun-Yong Lee returned to reprise another work, this time the wonderfully named “Snail’s Gallop” (pictured). Silence fell once more as the elderly artist crouched down and began to fill a 6-metre (20-foot) strip of paper with a zigzagging pencil line: what the hand drew, the feet smudged as he edged forward. Mr Lee emerged smiling, but the work spoke eloquently about life’s difficulties and the frustrations of daily existence.

"Rehearsals from the Korean Avant-Garde Performance Archive" continues at the Korean Cultural Centre in London until August 19th

https://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2017/07/happening-hanguk